One of the richest Americans in history, Andrew Carnegie was a steel magnate from New York whose wealth could compete against the pharaohs of old. And like most billionaires, Carnegie somehow managed to become embroiled in politics. As one of the world's richest men, Carnegie had the courage to call out the encroaching imperialism of the United States of America, as well as the privilege to call them out on it. One cause that urged him to oppose imperialism was a small smattering of islands on the other side of the world—The Philippines.

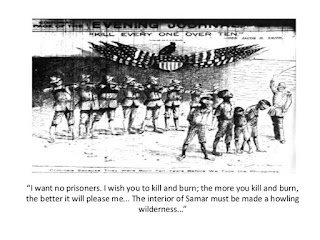

When the Spanish lost the Spanish-American War, the U.S. purchased the Philippines for $20 million as part of the Treaty of Paris, effectively annexing the country into the American colonies. Like Mark Twain and Leo Tolstoy, Andrew Carnegie opposed America’s involvement in the Philippines, calling out the government on denying Filipinos their independence. The move to purchase the Philippines contradicted the U.S.’ involvement in the Spanish-American War in the first place. The war began when the U.S. backed Cuban revolutionaries fighting for independence from the Spanish, but the U.S. sang a different tune when it purchased the Philippines from the Spanish, leading to the eventual Philippine-American War.

Carnegie was so against the act that in 1898 he offered to donate $20 million to the people of the Philippines so they could buy their independence back from the Americans. Take note, this $20 million would have come out the pocket of Carnegie himself, although it certainly wasn’t a dent in his wallet as Carnegie was estimated to have a net worth of $310 billion.

“Mr. Carnegie went to [then President William] McKinley when the Spanish treaty was pending, and said to him that America was in face of war in the Philippines; that our people and the Filipinos would soon be killing one another,” a 1902 article in the New York Times reported. “He asked to be sent to Manila with the fullest authority to declare that America desired good things for the little brown men and would soon recognize their independence.”

The Bud Dajo Massacre, 1904

MARK TWAIN AND THE PHILIPPINES :

CONTAINING AN UNPUBLISHED

LETTER

MORTO N N . COHE N

Although Kipling's "The White Man's Burden" is the most famous piece

of literature evoked by the Philippine phase of the Spanish-American War,

it is not only the utterance by a man of letters on America's venture into

imperialism. One of the most forceful voices heard on the subject on this

side of the Atlantic was that of Mark Twain, who held strong convictions

diametrically opposed to Kipling's. *

Twain's political opinions in general and his views of American expansion in particular have been well chronicled, but the account is enriched by

an unpublished Twain letter that has recently come to light and the unpublished letter from the admirer that elicited it.

2

At -the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, Twain was living in

Europe, lecturing and writing, his only means of earning enough- money to

pay the debts he had incurred when the Webster Company collapsed. While

abroad, he undoubtedly heard a good deal of criticism of his country's policy in Cuba. But he defended the United States' position, believing that

America was genuinely concerned for the Cuban people. He was not, however, sympathetic with the government's'attitude toward the Philippines,

for even before he returned home he saw that Washington did not intend to

give the Filipinos immediate independence.

He had, of course, read the reports of Dewey's victory over the Spanish

fleet in Manila Bay, of the Rough Riders' victory in Cuba, and of Spain's

capitulation to McKinley's demand that she relinquish the Philippines in exchange for $20 million. He also knew that the Filipinos had risen in revolt

when they realized that they were merely trading Spanish for American domination and that the United States had sent 70, 000 men to the archipelago to

defend Old Glory. He was certainly disturbed by the reports that American

soldiers has resorted to humiliating bushwhacking to route Filipino guerillas

and that atrocities had been committed by American prisoner-of-war camp

authorities.

He arrived back in New York on October 15,1900, to a tumultuous welcome, and he seized the opportunity, while in the limelight, to speak out

quickly and passionately against American imperialism. During his first

interview, on the evening of his arrival, he excoriated the government. "I

have seen, " he said, "that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the pie of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. "^

And when he spoke at a dinner in his honor at the Lotus Club on November

10, he again expressed anti-expansionist sentiments.

His was clearly a minority position. Imperialism, in the guise of Destiny, was the cry of the day, especially in the yellow Hearst and Pulitzer

press. Twain, at the height of his success, must have realized fully that

by embracing an unpopular cause he was jeopardizing the very audience upon whom he depended for a living. "Mark Twain feared a possible return

into debt as he feared almost nothing else,TT

Professor Gibson has written;4

and yet hardly a month passed in the three years after his return to this

country during which he did not, in one way or another, denounce imperialism. The more he read about American operations in the Philippines, the

stronger grew his indignation, the more frequent his outspoken appeals, the

more vehement his public denunciations. On December 13, 1900, at a Waldorf-Astoria banquet, when he introduced Winston Churchill, then a young

war correspondent, he interspersed his gracious compliments with frank

admissions that he and Churchill did not see eye to eye on imperialism, and

he restated his position on recent events in South Africa and China, as well

as the Philippines.

It is not surprising, in the light of his pronounced views and his obvious

desire to influence American policy if he could, that he granted a request

from the Red Cross Society at the end of 1900 to write a greeting which, he

understood, would be read on New Year's Eve, along with other messages

from famous people, at numerous meetings across the country. But after

he wrote his statement, he discovered that the Society was using only his

name in its advance notices, and he asked the Red Cross manager either to

publish the other names as well or return his contribution. The manager

returned the greeting, and Twain sent it instead to the New York Herald,

which printed a photograph of it in its issue of December 30, 1900. The

text reads as follows:

A salutation-speech from the Nineteenth Century to the

Twentieth,

taken down in short-hand by Mark Twain:

I bring you the stately matron named Christendom,

returning dedraggled, besmirched and dishonored from

pirate-raids in Kiao-Chou, Manchuria, South Africa, &

the Phillipines [sic] , with her soul full of meanness, her

pocket full of boodle, and her mouth full of pious hypocrisies. Give her soap &-a towel, but hide the lookingglass.

Mark Twain5

New York, Dec. 31, 1900

Professor Gibson has pointed out why this piece is perhaps Twain1

s

"most perfect single piece of persuasive writing" and has described the re -

action to it in some detail. " The hitherto unpublished material, a letterMark Twain and the Philippines 29

from an admirer and Twainf

s reply, give further evidence of Twain's strong

opinions.

The admirer was Abner Cheney Goodell (1831-1914) of Salem, Massachusetts, a lawyer and historian, sometime President of the New England

Historic Genealogical Society, who owned an exceptional library on witchcraft and was, at the time he wrote to Twain, an editor and annotator of

the laws of colonial Massachusetts.

7 He writes from Salem, on the same

day that Twain's greeting appeared in the Herald:

Dear Sir:

Will you forgive a stranger for obtruding upon your

scant leisure this expression of gratitude for your ''Salutation " to the incoming century.

In my opinion it is, so far as I know, the best thing

you ever did. Indeed, I rank it with Lincoln's immortal

speech at Gettysburg.

It has done me good. I have stopped taking medicine,

now that somebody has done something effectual to rouse

the public from their chronic apathy in this universal reign

of terror.

It is a great strain upon one's self-confidence to continue to harbor the conviction that he is right, and all the

"powers that be" of Christendom are wrong in their fearful onslaughts upon human beings And if wrong, how appalling the magnitude of the error of crime !

You have cheered me. You reassure me against the

depressing doubt of my own sanity, and you encourage me

to believe there is yet hope that-old Waller's sentiment,

echoed by Charles Sumner in the title-page of his first

great plea for universal peace, may prevail throughout

the world:--

'What angel shall descend to reconcileThese Christian states, and end their guilty toil?"

I implore you to continue to improve the advantage

which the high place you have attained gives you for reaching the public ear and conscience, by stirring up the pharisees until they stop, to think; which it would be distrusting the providence of God to doubt must be followed by re -

lenting and repentance.

I end, as I began, with the profound thanks of,

Yours cordially,

Abner C. Goodell

Mr. Samuel Clemens,

14 W. Tenth St. ,

New York, N. Y.

Tolstoy against the hypocrisy of the West

Like the members of the Anti-Imperialist League, Tolstoy condemned the Philippine invasion with the same ferocity as the suppression of the Boxer nationalists in China and the invasion of the Boer republics by Britain. He noted that these actions only demonstrated the hypocrisy of the West and its so-called discourse on freedom. Opposing the argument of the imperialists, Tolstoy wondered how countless atrocities could be committed in the name of civilization.

Unsurprisingly, the remarks of Tolstoy fell on deaf ears. Even in the standard historiographies of the Philippines, the Philippine-American War was skipped in favor of highlighting the material improvements under American tutelage. This partially stems from historians such as Rafael Palma and collaborators such as Pardo de Tavera who viewed America as a force for the greater good.

No comments:

Post a Comment